|

| Ontario Gothic, Charles and Maude Thorn in their home in Hillier, Ontario. |

THE STORY IN A PHOTOGRAPH FROM A POST FIRST WORLD WAR PERSPECTIVE

REVISITING A FAMILY PHOTO ALBUM FROM HILLIER, ONTARIO, PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY PART THREE

While looking, this week, at the turn of the 1900's family photo album, from the hamlet of Hillier, Prince Edward Country, Ontario, I happened upon, quite by accident, a unique overview of photography circa 1918. It doesn't detail how one should take a photograph, or pose subjects for portraits, but has an interesting, albeit juvenile generalization, of how image making is possible via a camera lens and the box, on which it is attached. I've worked in a darkroom myself, and been a news photographer for a weekly publication, and have read a lot of books on the subject, including Boris Spremo's photographic essay (inscribed and autographed by the way), but I have never found a more simplistic, yet effective way of explaining how an image is made permanent via a negative, and then onto sensitive paper to make a print.

"When we look upon the surface of a mirror, we see the image of ourself and our surroundings. The extent of the view depends upon the size of the mirror, and the distance we are standing from it. If we hold the mirror close to our face we see only the face, or perhaps, but a portion of it, and the farther away we are, the more the mirror will reflect, only, of course, the various images will be smaller. The mirror reflecting exactly what the eye sees, without doubt, had a great influence in inducing the experiments that resulted in the process we call photography."

This information was contained in the post First World War self help book, entitled "The Book of Wonders," published by the Bureau of Industrial Education, in Toronto. It was meant for a younger audience obviously.

The text continues, by noting that, "The taking of a photograph with a camera may in a way be compared with the action of your eyes, when you gaze upon your reflection in a mirror, or look at any object or view. Any object in a light strong enough to render it visible, will reflect rays of light from every point. Now, the eye contains a lens very similar in form, to that used in a camera. This lens collects the rays of light reflected from the object looked at, and brings them to a focus in the back of the eye, forming an image or picture of whatever we see, just as the mirror collects the rays of light and reflects them back through the lens of the eye. Certain nerves transmit the impression of the image, so focused, in the back of the eye, to the brain, and we experience the sensation of sight."

The 1918 circa text goes on to explain, "What is the eye of the camera?" The answer the book gives is as follows: "The lens is the eye of the camera and the process we call photography is the method employed, to make permanent the image the eye, or lens of our camera, presents to a sensitive surface with the camera.

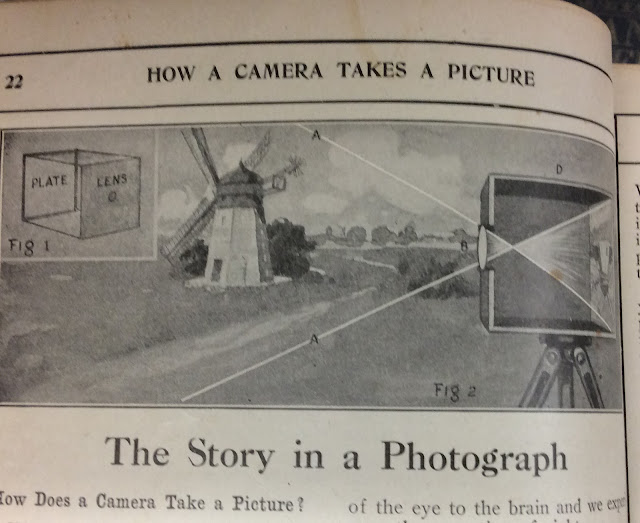

"Figure one (illustrated above today's blog), shows a simple form of camera, it being merely a light-tight box with a lens fitted to the front, and a means for holding a sensitive plate at the back; the plate being placed at just the right distance to focus the rays of light admitted through the lens, in exactly the same manner as the rays of light pass through the lens of the eye, and comes to a focus in the back of the eye. Now, if we could look inside the camera, we would note that the image was inverted, or upside down. The rays of light from "A" pass in a straight line through the lens "B" until they are interrupted by "C," upon which they strike, forming an upside down image of the object "A." But, you exclaim, 'we do not see things upside down.' No, we do not, because some mental process readjusts this during the passing of the impression from the eye to our brain.

"Let us suppose we have our camera loaded with its sensitive plate or film. We select some objects or view we wish to photograph, uncover the lens for an instant, and let the light impress the image upon the sensitive surface of the plate or film. Now, how are we going to make this image permanent. If we were to examine the creamy yellow strip of film upon which the picture was taken, there would seemingly be no difference between its present appearance and before the snapshot was made. Now let us suppose that this strip of film is a little trundle bed (a smaller bed tucked under the master bed, for children to sleep), and in it tucked securely away from the light, are many hundreds of little chaps called silver bromides; little roly-poly fellows lying just as close together as possible, and protected by a coverlet of pure white geletine. Until the sudden flash of light in their faces when the picture was taken, they have been content to lie still and sleep soundly. Now they are seized with a strange unrest, and each little atom is eager to do his part in showing your picture to the world. Alone they are powerless, but they have, all unbeknown to them, some powerful chemical friends, who, organized and aided by the photographer, will bring about their transformation. These chemicals, with the help of the photographer, form themselves into a society called 'the developer'.

The text carries on, reporting "The photographer takes just so many of the tiny feathery crystals of pyro, just so many of the clear little atoms of sulphite of soda, and just so many little crystals of carbonate of soda, and tumbles them all into a beaker of clear, cold water. Unaided by each other, any one of these chemicals would be powerless to help their little bromide of silver friends. The first of these chemicals to go to work is the carbonate of soda. He tiptoes softly over to the trundle bed and gently begins turning back the gelatine covers over the little bromide of silver chaps, so that Pyro can find them in the dark. It is Pyro's mission to transform the little silver bromides into silver metal, but his is rather an impulsive chap, so he is accompanied by sulphite of soda, who warns him not to be too rough, and whose sole mission is to strain his eagerness, to help his friends. 'Go slow now,' says Sulphite, 'don't frighten the little silver bromides, or else you'll make them cuddle up in heaps, and the picture won't be as nice as if you wake them up gently and each little bromide stayed just where he belonged.' After all the little bromides that the light shone on, have been transformed into metallic silver by the developer, another chemical friend has to step in and carry away all the little bromides that were not awakened by the flash of light. This friend's name is 'Hypo,' and in a few minutes he has carried away all the little bromides that are still sleeping, so that the trundle bed with the now awakened and transformed silver bromides will, after washing and drying, be called a negative, and ready to print your pictures from.

"If we take this negative, as it is called, and hold it up to the light, we will see that everything is reversed, not only from the right to the left, but also whatever is white or light in color is dark in the negative, and that what would correspond to the darker parts of our picture, are the lightest in the negative, and it is from these facts that we give it the name negative. Now, to get our picture as it should be, we must place this negative in contact with a sheet of coated paper that is also sensitive to light. So we place the negative and the sheet of sensitive paper in what is called a printing frame, with the negative uppermost, so that the light may shine through the negative, and impress the image upon the sheet of sensitive paper. Now, it stands to reason, that if the lightest parts of our picture, are the darkest in the negative, that less light can pass through such portions of the negative in a given time, so that with the proper exposure of light the image upon the sheet of sensitive paper will be a correct picture of whatever the lens saw."

In today's pictures, taken from the early 1900's family photograph album, having originally belonged to Charles and Maude Thorn. of Hillier, Ontario, we have taken a page from the book, showing Charles and Maude in their new automobile, with companions Alida and Jim in the back seat. In the photograph to the left, Maude Thorn stands in a field with their dog Barlo. In the other grouping of album photographs, there is a foggy image of the Thorn homestead, in Hillier, dating back to 1860, located on the 32nd Concession. The group photo on the bottom right, shows "George and Florence, Lil and Fred, Alida and Jim. On the bottom, the lady sitting at the tea table is Maude Thorn. In the grouping of four, Maud appears on the bottom right, sitting with arms folded. The interesting portrait of Maude and Charlie, in the doorway of their homestead, was run in a group photograph last evening, on this page, but a mysterious white cloud, a ghost possibly, covered over their faces. The picture has been republished above. There are several other group photographs being run today on our Currie's Antiques facebook page, from the same album, showing the "McGuiness Boys," we believe, the elder boy being in the sailor's uniform, with rank of Petty Officer. We have attempted to blow-up the image of the tally on his sailor's cap, but all we can make out is "HMCS," and the first letters of the ship's name, which could either be the Canadian Navy ships, the "Nabob," "Nanaimo," or the "Napanee". It appears the youngster is wearing the white sailor's cap, shirt and trousers, also belonging to his brother. What a great photograph, of Second World War vintage. There is no indication if the McGuiness Boys were related to the Thorn family, but these photos were prominently displayed in their album. If you look closely at the succession of three snapshots, you will see the elder McGuiness, holding a small dog in his arms.

When you find great photos like these, and realize they could well have been discarded by a former owner, all you can think about, and question, as you go through the pages, is whether companion photo albums from this same family, were destroyed, or sold off at sales, to those who possibly won't appreciate the provenance; or that there may be family members out there, very much interested in a repatriation of these important keepsakes.

It's not always possible to attach a meaningful provenance, on otherwise unidentified vintage photographs. If they had been kept in their albums, with a connection with regions and studio photographers, there's always a chance the photo sleuth can localize some of the images; such as if there are photographs of churches, or public buildings that can be identified, as to location, and even one name, can give us room to start an online search.

A trend began about thirty years ago in the antique trade, to remove old photographs from beautifully adorned albums, many from the Victorian era. There was the mistaken idea, that a modern consumer, with an interest in vintage decorations, would buy the old, vacated albums, to insert their own family relics. In other words, dealers and second hand shop vendors, thought it would be more profitable, to sell the albums separately, and the photos harvested from within, could be sold for between a dollar each, upwards to four or five dollars. It was assumed, with fifty to a hundred photos, they could make several hundred dollars on the images, and fifty bucks on the empty album.

They were wrong of course, because few wanted the burdens of the Victorian era, transposed onto their contemporary families; because honestly, the old albums have a mournful appearance, suited to the period they were popular. The cabinet photos, and larger format images, were hard to sell, unless they had a unique background, such as identifiable architecture; or were of military significance, such as subjects wearing Civil War uniforms. Thus, many of the photographs went unsold and were added to, giving these dealers a lot of dead stock to contend. The number of antique lovers who buy unidentified photographs like this, is very small, for the millions of antique images still flooding the market. The point of stating this, is that the possibility of identifying the images were lost forever, when the integrity of the albums was sacrificed, for the sake of increased profit. It never happened. As it is, I will only cherry-pick the images in these shop collections, that have obvious historic merit, and represent the work of a photographer from a region of which I am familiar. There are of course, quite a few studio names and photographers I look for, especially those from Muskoka, because we have many local collectors interested in regional content.

There's a profoundly haunting sensation, when you can actually make the connections in old photo albums, expanding on the minor amount of information usually contained in the few words of captioning, and some minor notes often penned onto the backs of the images. It's as if the book itself, is trying to assist the identification process, although I can't really explain this phenomenon. It's just a feeling you get, and the joy you feel, when online referencing turns up unexpected provenance, that may start out with one lead, and then lead to hundreds; and before long, you have a preamble story, which is better than nothing. I have lot of those albums as well. We never give up trying to discover something, anything about these unidentified albums, but there's still no way we would ever dispose of them. We're the only family they have now, and we have lots of room for them to lodge with us, at Birch Hollow. Every now and again, Suzanne will remove a few examples, and re-photograph them, to use on our "Currie's Antiques" facebook page, where their personalities can shine once more.

Please don't throw out old photographs. Give them to someone who cares for such visual histories, and likes the idea of being new age, adopting kinfolk, to keep them relevant in a modern perspective.

No comments:

Post a Comment